By Goh Huck Heng

Goh Huck Heng (Goh): Landscape painting (shan shui) is regarded as the highest form of Chinese painting.

Artists use a variety of brush strokes called Cun (methods for creating wrinkles) to create the textures of mountains and rocks, like Pi Ma Cun* for creating soft and parallel lines and Juan Yun Cun** that creates curved lines mimicking cirrus.

There have been many great artworks featuring landscape in Chinese history, but speaking of freehand style (Xie Yi), it pales in comparison to the works of Japanese artists like Sesshu Toyo of the Muromachi period.

Tan Oe Pang (Tan): Sesshu has reached the zenith in freehand style landscape painting. His works are heavily influenced by Liang Kai, Mu Xi, Ma Yuan, Xia Gui and other Chinese artists of the Song and Yuan dynasty. Sesshu brought the then popular Zen painting to unprecedented heights.

“Zen painting” refers to a genre of paintings that embody the philosophy of Zenism, combined with the characteristics of literati painting***. They are not confined to any particular form or style.

Zen painting artists seek the inner realities and express their own lofty spirits instead of pursuing realism.

Sesshu’s freehand landscape paintings manifest profound wisdom through simple and unadorned brushwork. He likes to use asymmetric composition and expresses the Zen spirit by leaving large areas blank (liu bai), which creates a sense of distance and vagueness. Looking at his paintings, one can feel the tranquility, elegance or even an air of lonely silence from the simplicity in their design of space.

Goh: Sesshu expresses his observations of the world and his understandings of life through simple brushwork. His Zen paintings are really outstanding.

However, it seems to me that his landscape paintings are too ethereal while lacking a sense of weight and substance. This painting of yours contains more elements of art than Sesshu’s.

Tan: Sesshu’s line drawings are not round, thick and solid enough, but a bit light and impetuous.

Though simple, fresh and containing the Zen spirit, his paintings are more like literary compositions instead of philosophical enquiries that lead one to search deep within and seek the primordial.

Goh: It is really hard to use “atmospheric perspective” (san-yuan) to create illusions of distance and space in freehand landscape paintings. How do you resolve this issue?

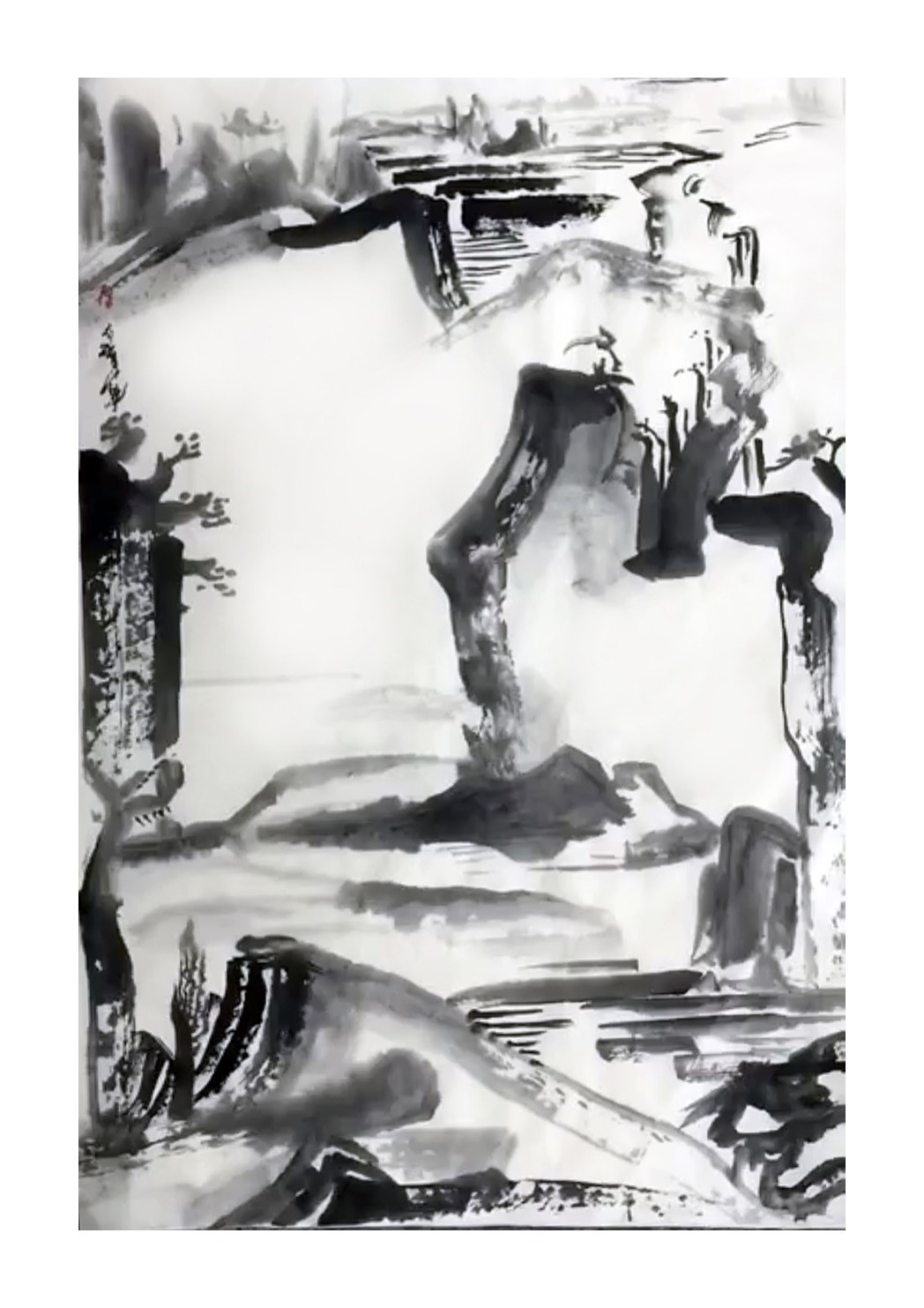

Tan: Perceptions of distance, depth and breadth of space are delivered via this little space at the top part of this painting where I drew the remote mountains.

The traditional Cun method (wrinkle creating method) was not used due to the limited space.

Instead, I used centred-tip brush strokes that switch between gentle and solid, dark and light, thick and thin, ambiguous and definite lines to depict distant mountains of different shapes, with each shape corresponding to one of the five elements (Wu Xing) – round (representing metal), straight (representing wood), curved (representing water), pointed (representing fire) and square (representing earth).

The five elements mutually generate and mutually overcome one another.

As the peaks and the bottoms of the mountains unfold, one can imagine how grand the landscape being depicted is.

Without painting the distant mountains in the background, the whole scene would not be as grand as it is now.

I used thick lines that convey a rich feeling of texture and volume to contour the near mountains, and varying brush strokes, pitching, pause and transition to present the undulating mountains in the distance.

The cliff on the left formed by solid lines was created with thick ink application, and the trees on the cliff look just like the real ones.

Centred in the painting, a combination of curved and straight lines formed the outline of a mountain.

The outer lines are clear and definite while the inner ones are rather ambiguous, creating a rich sense of texture. The lines turn at sharp angles to convey the steepness of the mountain.

Right beside is this line, stretching from the bottom to the top, and then turning left.

Initially, thick ink was applied to create lots of volume, followed by light ink creating lines that carry a sense of continuity despite several pauses.

The line connects to the distant mountains at the top, allowing the artistic theme to flow throughout the painting.

Round lines are used to draw the curved tree branches. These simple lines delineating the trees remind one of the simple, artless and original nature of lives, the most truthful state of life.

Right after those lines is a thick line sketching that looks like a vajra. As it extends further downward, the lines get lighter and dimmer, creating a rusted texture.

Delineated using centred-tip brush strokes, rapid, round, brisk and neat, the waterfall at the upper right corner painted against the white xuan paper looks as if it is emerging from the clouds and mist and then hides itself among the mountains again.

The mountains come alive with the waters surrounding it, revealing an overflow of vigour.

A hill lies at the bottom of the painting, composed of three left-falling brush strokes of thick ink with a neat outline but dentate inner lines, and one right-falling stroke painted gently with mild amount of ink.

Thick curved lines form the small hillside at the very bottom.

The hollows in the brush strokes (Fei Bai) look like the footprints that birds and beasts leave behind after taking a stroll in the hill.

Two trees stand to the left of it.

The one nearer to the hillside is extremely simple and plain, just like a “unicellular tree”, invoking viewers to imagine the origin of time when everything was first created.

The tree further away from the hill occupies a large space, displaying plain and unadorned beauty, creating a sense of the primordial.

In between the mountains, the ones that are nearer to and the ones that are further away from the viewers, large blank areas resemble the clouds and the void.

The white belt resembles floating clouds surrounding the mountains, accentuating the mountains’ height and steepness and adding a sense of motion to the painting.

The altitude, the profound depth and the broadness created set the grand scene of the painting which was further enriched with refined details.

The whole painting reveals a pure, peaceful and detached realm.

Goh: With simple and natural brushwork, the painting creates a world so clear and bright, conveying deep conception despite its clean and simple layout.

Breaking through from all past works, the painting embraces the primitive nature of time, space, and purity and charm in the forms of life.

I’d say that this work will provide a benchmark for the future of Chinese painting for generations to come. One can feel the boundless inner world of the painter while viewing it.

Tan: Paintings convey the artists’ perspectives towards life and the world, which manifest in the viewpoint of the artist while producing their works, and in the selection of subject, theme, art form and techniques.

Since I started studying Falun Buddha Law****, I have gained a deeper understanding of the structures of space, the beginning of unlimited primeval nature, the beginning of time and the beginning of all shapes.

Forgetting about the distinction between the objects and the self, I am able to feel and experience everything whole-heartedly and present my grandest and deepest understandings of life and objects in simple and plain forms.

Paintings like this remind one of the earliest, the beginning of all memories, the primordial state.

The mountains, trees, clouds, and waters are all at their earliest, purest and most original forms.

Without a clear and broad mind devoid of worldly attachments, it is hard for one to appreciate the grand realm presented through the painting.

It is very rare to have the primitive nature of time, space, and the purity in the nature of life, and charm and form presented all together in one single painting.

Really very rare.

Goh: The painting is not restricted by any standardised forms and styles commonly seen in landscape paintings.

Simple brushwork outlines the shapes of objects, with the focus on the spirit conveyed through them. Viewing it is like standing on the mountain top capturing all under the sky with one’s eyes, like divine beings contemplating the earth.

Everything is pure and clean.

The original article is in Chinese. It was translated and edited for publishing on Epoch Times.

Other artworks by Tan Oe Pang

Editor’s Note

* Pi Ma Cun was first used by Dong Yuan and Ju Ran from the Five Dynasties (907 AD – 960 AD).

** The most well-known artwork that largely applies Juan Yun Cun is the Early Spring by Guo Xi, a Chinese painting master of the Northern Song Dynasty.

*** Literati painting denotes a school of Chinese painting comprising art created not by professional artists, but scholar-bureaucrats who sought to express the inner world rather than merely depict the appearance of things.

**** Falun Buddha Law: a Chinese spiritual practice that combines meditation with a moral philosophy centered on the tenets of truthfulness, compassion, and forbearance.

For further appreciating Tan Oe Pang’s paintings, visit Sky One Art Gallery.